CAPTAIN BLIGHT

This is an article from the Kansas City Pitch Magazine, and my response.

Captain Blight – by Casey Logan

https://www.thepitchkc.com/captain-blight/

“On the day of his 303rd conviction, Charlie Williard walks into Courtroom I in the Kansas City, Missouri, Municipal Court Building, takes a seat in the corner and waits for a lawyer who has forgotten to show up.

The day before, in a law office just two blocks from the courthouse, Sean Pickett had joked about the difficulty in keeping track of his client’s prodigious legal entanglements. “He’s got court dates all over the place,” he’d said. “I can’t keep track of them.”

Now, on November 19, as jailhouse defendants appear one by one on a television mounted in the courtroom for arraignments on crimes from the mundane (pot possession) to the dazzling (pistol-whipping a man named Littlejohn), Williard waits with the unflappable posture of an old man sitting on a park bench. He has a style in clothes that will one day fit nicely on the racks of a vintage-clothing store — snap-button dress shirts and poly-blend slacks a few sizes too big. Five grubby, callused fingers emerge from a cast on his arm to limply shake the hand of a bailiff who recently bought a water heater from Williard. The hair on his head is solid white; grayish strands dangle from his ears and nostrils, begging to be yanked by a tactless child.

No one knows how many times Williard has appeared in municipal court, least of all Williard. He estimates somewhere between 200 and 300 times and thousands of dollars in fines for violations of the city’s housing codes. What is known is this: Since 1980, Williard has been convicted 302 times. Today marks 303.

Most people do what they can to avoid going to court. They’ll pay a parking ticket by mail, however irritating, just to handle the matter and move on. But in Williard’s view, court is no more inconvenient than stopping for a red light. He’d rather pass on through, sure, but then again, what’s a little wait?

That stubbornness in the face of repeated hassles has turned him into a pain in the ass for everyone aiming to cure the world of his malignance — neighborhood associations, codes inspectors, prosecutors and judges. In the eyes of the law, he’s a criminal, and the government’s only recourse is the judicial process. If a man demonstrates no fear of that process or its penalties, what chance does the state have? If he takes a perverse pride in his 300-plus convictions, if he’s willing to toss off $500 fines like quarters into a cussing jar, at what point does it all become a joke?

Williard’s code-breaking rap sheet dates back 23 years, but his nastiest battle with City Hall reached a ten-year anniversary this October. Back in 1993, the city’s municipal housing court judge, fed up with Williard’s perpetual offenses, sentenced him to three and a half years in prison and fined him $12,500. Williard fought that ruling and won on appeal. In the end, he paid $5,000 and served twenty hours of community service.

Five years later, the city tried a new strategy, designating him as Kansas City’s first “Slumlord of the Month,” a ploy that made for decent TV news but did little to disgrace its recipient, who still refers to the title as an award and an honor.

Then, earlier this year, city attorneys tried putting Williard out of business altogether, filing nuisance charges against him and slapping injunctions on the majority of his properties. Unfavorable court rulings forced the city to drop the matter and, after several months, lift the injunctions. For the moment, the city has backed off.

Now, with this morning’s hearing just a guilty plea and a $500 fine from being settled, Williard finds himself in the somewhat atypical position of having no pending charges against him. If you think he revels in this fact, that he will savor this legal quietude after so many years of tumult, well, then, you don’t know Williard. Not yet.

Like an old boxer playing the ropes, Williard has spent nearly a quarter-century letting the city swing away at him, absorbing some shots, avoiding others, waiting for his opponents’ hands to drop from fatigue. Now he’s swinging back. On December 3, Williard planned to file a federal lawsuit accusing the city of targeting him unfairly, of violating his constitutional right to equal protection under the law. He accused the city attorney and housing court judge of conspiring to destroy him by molding the judicial process. After years of making a mockery of the system as a defendant, he’s turning the tables on the city.

But back on November 19 at 11 a.m., in the courtroom of the Honorable John B. Williams, Charlie Williard stands, pleads guilty to yet another codes violation, number 303, and retreats to the court cashier to pay his fine.

“How much will that be?” he says.

“Five hundred and twenty-nine dollars and fifty cents,” says the woman behind the glass.

“What’s the 50 cents for?” Williard says, smiling.

“Oh, just because.”

Williard laughs jovially and opens a thick wallet. Without flinching, he removes a stack of bills, hands it over, then heads across the street to the Jackson County Courthouse to garnish the wages of a delinquent tenant.

To get an idea of what kind of ornery son of a bitch the city is dealing with, consider the frightening image of Williard driving his young family to Kansas City in 1967 in a seventeen-year-old Dodge pickup truck with no side glass, chugging along through a pouring rain, water splashing on the tiny face of his formerly sleeping and now terrified infant daughter, with Williard himself half-leaning out of the cab to clear the windshield with a handheld wiper he’d fashioned from a coat hanger.

“I moved here to work for Phillips Petroleum, and I bought a house at 3421 Holmes,” Williard recalls. “The one beside it came for sale, and I bought it. And then Phillips moved their operation to Bartlesville, [Oklahoma], and I just stayed here working those properties and working for other property owners doing maintenance. And I bought and sold cars. And I then just bought more properties as time went by.”

The time going by was marked with a fear spreading across the country, as white families deserted their neighborhoods to avoid living among the black families moving in. As property values plummeted, thanks in part to opportunistic realtors who played whites against blacks, Williard amassed several properties at prices that sound unbelievable today. One house, he says, cost just $250. For years, Williard collected rent on these properties.

By the early 1990s, however, whites began to flock back to the city. Undaunted by the task of restoring old homes, encouraged by reasonable price tags, a legion of urban enthusiasts revisited midtown and started giving Hyde Park a scattershot makeover. The area fractured into different neighborhood associations that now tout the number of rental properties converted back into single-family homes.

Some areas did better than others. While the area south of Armour Boulevard prospered, the area north didn’t fare as well. And square in the middle of that was Williard.

“Part of my situation is because my properties are right in a little circle, and a very vocal few down here in South Hyde Park would like to have gotten richer with their properties,” he says. “And so they made themselves known, because I was in their way. North Hyde Park had not taken off like South Hyde Park. The why of that, I don’t know. Armour is part of the problem…. This area hasn’t taken off like South Hyde Park. Part of it may be that I own a dozen properties in here and I haven’t been willing to run the rentals out and turn it back into single-family homes.”

In fact, that’s exactly the reason the area lags, according to some of Williard’s neighbors — that and the manner in which he maintains his properties. Williard speaks of his numerous codes violations as if all of them centered on peeling paint or the storage of “unapproved items,” but the truth is that codes inspectors have tagged him for deficiencies far worse, including reports on two properties in such disrepair that the city tore them down.

Williard continues to frustrate many of his Hyde Park neighbors. Earlier this year, Dan Mugg relocated from Quality Hill to a house near 34th Street and Holmes, just down the street from Williard’s own home and encircled by the landlord’s properties. In eight months, Mugg invested $25,000 in his new home, a commitment that left him feeling all the more resentful of his unseen neighbor.

“You feel you’re between a rock and a hard place,” Mugg says. “I didn’t realize I was buying a house surrounded by slumlord property.”

Then he got accustomed to the signposts of a Charlie Williard neighborhood: interior furniture on outside porches, unkempt lawns, backyard toilets and sinks, tenants’ dogs running wild, cockroaches sent scurrying into adjacent homes by the perfunctory spraying that follows inevitable evictions, drugs.

“There’s only been one crystal meth lab,” Mugg says, laughing.

If Mugg has retained a sense of humor about Williard, it’s not without a telling dark side. “I tell people I never wanted anybody to die before,” he jokes.

The frustrating part, Williard’s critics say, is that he seems impervious to any pain the city tries to inflict. “The system just isn’t able to deal with the hardcore ones like Charlie,” says Dona Boley, a Hyde Park resident who tracks codes violations surrounding Troost Avenue. “The city’s ordinances just don’t have enough teeth.”

But how much tougher could the city be? In 1993, Municipal Court Judge Wayne Cagle sentenced Williard to more than three years in prison — a harsh judgment for any municipal court. Though Williard avoided the full term of that penalty, he spent hundreds of days in county jail for his obstinacy. And at 68 years old, he still acts as though he’s prepared for more.

Williard’s success isn’t in circumventing the system but in rendering that system powerless to stop him. For all his defeats, he keeps going, buying houses here and there, fixing them up just enough to turn a buck, and fighting off detractors with the persistence and rigidly fixed logic of a robot.

There is something almost religious about the reasoning Williard employs against his nemeses. Not Jesus religious, but rather a kind of moral certitude that he believes transcends the law. Instead of bilking the poor, Williard says he serves them. He fights off gentrification with his unbroken hand while providing affordable if imperfect housing with the other. His properties might not be beautiful. There might be trash on the lawn and cracks in the siding. But they’re cheap. And there’s a need for that. Always will be.

“There’s a place in our economic system for the Rolls-Royce, the Cadillac and the Ford,” Williard says. “They each serve a need. We could carry this code enforcement into the vehicles we drive, and if the vehicle has some rust on it, get it off the street. When we do that, we’re going to eliminate the low-cost car.”

There is actual dread in his voice as he says this. Williard believes the time will come when consumers no longer buy their cars but lease them from a handful of major manufacturers. New cars will have to be leased every few years, eventually eliminating the sort of junker that brought Williard to Kansas City in the first place.

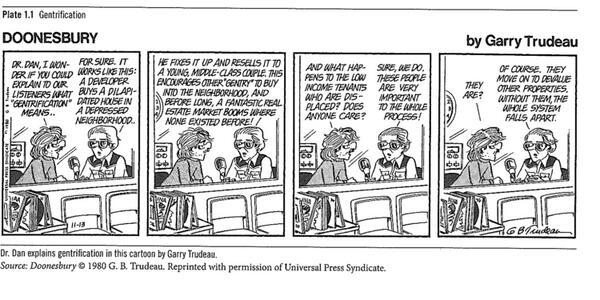

Naturally, Williard has a special hate for gentrification, which he sees as an unnatural, government-aided phenomenon so detestable that he carries around a Doonesbury cartoon that mocks it. He blasts people like Mugg for buying into affordable neighborhoods and then complaining about the very factors that made them affordable in the first place. He also slams Bill Clinton, whose move into Harlem drove up property values and made certain areas unaffordable to people who had lived there for a long time. And why? Because Clinton wanted Harlem, he says.

Coming from Williard, this particular argument seems a tad contradictory, considering that when pressed to defend his position — which, stripped of its florid shell, holds that “stuff should be left alone” — he resorts to a form of word parsing that could be described only as Clintonesque.

“Well, let’s define code violations,” he says one day about his innumerable offenses. “Is a little peeling paint on a house ‘detrimental to the health, morals and welfare of the people’? My van is parked on my grass out there. That’s a code violation. A year ago, I would have been cited for that. Maybe we need to redefine what’s a code violation worth, a $500 or $1,000 fine, and just leave some stuff alone.”

Later, Williard on being called a slumlord: “Well, let’s define the word slumlord. Normally, you think of a slumlord as a man who takes property in the slums, does as little to it as he can and milks it for all it’s worth, doesn’t care anything about the tenants and their problems. I don’t think I fit that situation. I think I run good, solid housing. It’s safe, well-wired, it’s well-plumbed, and the roofs are good. They can have some peeling paint, trash and debris, and storage of unapproved items without being a threat to the health, morals and welfare of the people.”

No one pretends that Williard’s properties are sparkling, not even the man he has hired to fight the city for him. “They’re not the most favorable living conditions sometimes, but Charlie is not charging a lot of money, and it’s someplace where the people don’t have to live on the streets,” Pickett says. “Some people would champion him. Others would say he’s a slumlord.”

Pickett says Williard has been harassed. In compiling his case against the city, the lawyer claims to have uncovered a system that works one way for Williard but another way for everybody else. Usually, codes inspectors cover entire areas of the city. In his client’s case, Pickett intends to prove, the Codes Department assigned an inspector whose sole responsibility was ticketing Williard.

He also accuses Cagle and city attorney Galen Beaufort of conspiring to target Williard unfairly. “Charlie spouts things here and there, and he talks about gentrification and these types of things, and whether you believe those things or not, that’s not what this case is about,” Pickett says. “This case is about the city taking extraordinary steps as to certain citizens, in this particular instance at least one citizen, in violation of their civil rights.”

Cagle declines to speak about Williard specifically. (Missouri law prohibits judges from commenting on impending cases.) Still, Cagle says he’s unconcerned by the threat of a lawsuit and believes his work on the bench has benefited neighborhoods.

Pickett argues that Cagle has stepped over his bounds to punish Williard. “He follows certain warrants and certain cases after he is no longer on the case, when they’re appealed,” he says. “He pressures prosecutors when the cases are on appeal, and if the prosecutors decide to get rid of a case on appeal, he will chastise them, or has in the past, and let them know in no uncertain terms that he does not approve of their actions when he has no jurisdiction over the case at all at that point.”

In March 2002, Williard hired Pickett to defend him in court and advise him on legal matters. In the past year, however, Pickett has learned that on certain matters it can be impossible to change Williard’s mind. He thinks he’s done so regarding his client’s most recent fight with the city, over a dilapidated warehouse near 33rd Street and Troost that remains a structure only by the loosest definition of the word. But Pickett is mistaken. Williard still considers that battle worth fighting. It isn’t the first time Williard has disregarded his attorney’s advice.

“I’ve been telling him for a year, almost two years come March, that he needs to change his lease to protect himself against the city,” Pickett says. “He has to put all the responsibility for the outside trash and those things on his tenants. ‘They’ve got enough trouble,’ is what he says. ‘They’re trying to get over drinking, they’re trying to get over drugs, they’re trying to get back on their feet.’”

Williard operates his business from a house smack in the middle of his rental empire, on a tiny street near 34th Street and Holmes. Vans sit cramped in an uneven driveway. Machinery and other debris lie idle on the front porch. Inside, a small path of carpet leads from the entryway to Williard’s office. Other than that, the first floor is covered with belongings stacked knee-high in all directions. The sheer volume blurs these items into a collective mass, with the unexpected exception of an electric guitar that stands upright against a wall. Williard plays the electric guitar.

The office itself contains two massive, broken-down copy machines that consume much of the room; a fax machine; a phone; a whirring lamp; a file cabinet; and a fairly new computer. Though Williard claims not to be computer-literate, he’s anything but a technophobe. On average, he types a letter a week to anyone he deems an appropriate subject for his unique brand of social commentary; more often than not, his recipients are The Kansas City Star and various City Council members. He has an associate publish the letters on his Web site ( affordhousing.com), which advertises his properties but mostly provides a platform for Williard’s off-key, libertarian rants.

“There is a place in our society for a slumlord if there is a place in our society for a liquor store to sell liquor,” he says, sitting at his desk and drawing upon one of his favorite analogies, along with pornography and guns. “The slum housing that a slumlord may provide is not any more detrimental than Colt 45 in a can. Maybe not nearly as detrimental.

“It would be kind of hard to say whether I take it personally, whether I’m irritated by being called a slumlord,” he continues. “I don’t think the people who know me call me a slumlord.”

Including tenants?

“Yes. Now some of them will call me that when they’re leaving and I’m after their rent. When they’re behind in rent, they will use that accusation.”

Halfway into an oration covering various subjects, all of them tied loosely together by a gentrification thread that disappears and reappears with little warning, there’s a knock on the front door. Williard waves in a female tenant who begins rambling nonstop. She is middle-aged and hyperactive, and she’s here to pay a portion of her rent.

“Can you cash this check?” she asks. “It’s like only $162.”

“How much money do you need back?” Williard says.

“Um, just the $62. I’m going to give you the $100. I gave $70 last week. I was going to give you $130, but if I do that, I’m going to be broke, so I’ll make up for it next week. Is that OK?”

Williard nods, opens a receipt book and starts scribbling.

“See, I get paid cash for the weekends anyway — ”

“Yeah, right — “

” — so I might just bring the other $30 Monday. You know, because I’m costing you $100 a week, and last week I only gave you $70.”

Williard opens his wallet. “So you need how much back?”

“Just $62. I ain’t worried about the change. It’s for $162.58, but I don’t care about the change.”

He places a few bills on the desk. “There’s $60,” he says. “And I think I have two here.” He flips through his wallet, but it offers only large bills. “No, I don’t have,” he says. “Remind me next time, and I’ll give you an extra two.”

“When you get a chance,” the tenant says, “go through and see how much that I have paid, because I actually haven’t been keeping track of it. I kind of know. I think this makes $500 or $600, but I’m not sure.”

“OK, all right,” Williard says, and finally shoos her away. He sets aside the check for $162.58 and says, “Now where were we?”

The latest in Williard’s long list of battles with the city centers not on a rental property but rather on the warehouse near Troost that he wants to turn into a storage facility and scrap yard. It is this issue that earned him his 303rd conviction, and by appearances it seems one both lost and worth losing.

Four walls surround the structure, which is about half the size of a football field, but a giant section of the roof has disappeared. Inside, it feels like an enormous, abandoned courtyard, with piles of wood, scrap and trashed appliances strewn about like forgotten toys. On an early fall day, a swift, metallic breeze swoops in.

The warehouse demonstrates how Williard and city inspectors can look at the same property and see two entirely different things. Whereas one sees a workable project — Williard claims he can replace the roof and fix everything else for $40,000 — the other sees the very definition of a dangerous building, one that presents myriad ways a person can be injured or maimed. Williard has already made improvements, but he blames the city for keeping him from completing the task.

When city attorneys filed injunctions against several of Williard’s properties, they put banks on notice that the properties were under dispute. The city argued that the injunctions were the result of Williard’s not fixing up his buildings as the law required. Williard maintained that the injunctions kept him from fixing them by keeping him from borrowing the money to complete the work.

“It wasn’t the most dangerous building in town, but it didn’t have a roof on it, and it looked terrible,” Pickett says. “It wasn’t necessarily dangerous to people on the streets. But if you decided to climb Charlie’s walls and get in the property and trespass, then something might fall on your head. Nevertheless, they knew Charlie couldn’t get any money of the type needed to do the roof, and they proceeded on the destruction and tried to demolish the property.”

Even with the injunctions lifted, Pickett says that a technical mistake has put his client in a poor legal position to fight for the warehouse, and he has advised Williard to forget it and move on. Ted Anderson, the assistant city attorney who inherited the thick Williard file a year ago, says that if the landlord doesn’t demolish the warehouse by December 9, the city will do so at Williard’s expense.

Nonetheless, Williard claims that the fight is still on, and there’s reason to believe that his federal lawsuit against the city has as much to do with this building as it does his 23-year history of codes violations.

“His particular point of view is that he may not win, but his argument is right,” Pickett says of that lawsuit. “So regardless of what the case is, his arguments are correct. If he doesn’t win a case, he has no qualms about it, but he wants everyone to know what’s going on.”

A few weeks before conviction 303, Williard takes a drive through his neighborhood in a white van that, like his home, is as much pack-rat storage as anything else. Pipes, empty hardware packages, scraps of aluminum foil, lightbulbs, plastic cups, a pair of pants, lamps, work gloves, tools, brooms, paint buckets — all of this is piled throughout the van in the fashion of a congested closet in some cartoon. Somewhere, a bowling ball surely lurks.

These days, Williard rarely has riders, so the search for a passenger-side seatbelt clasp ends in failure. Williard navigates his shock-prone van through the one-way streets and minefield alleys of his neighborhood, pointing alternately to the strengths of his own houses and the weaknesses of neighboring properties. “If you look hard enough, you can find something wrong with them,” he says of his rentals. “And yet, they’re good, solid houses.”

The tour carries on for blocks and blocks, through a depressed section of Hyde Park littered with kitchen appliances and houses that appear to be rotting from the inside out. He drives down an alley and points to a house that’s barely a house at all, then to a truck full of garbage parked in someone’s backyard. “I would be cited for that,” he says.

It’s not that he’s complaining about the shack or the truck. Really, he doesn’t mind. In court on November 19, when he mentions a neighbor with worse violations than his, an inspector tells him to report the guy to the city. “What’s the point?” Williard says. “He’s not hurting anybody.”

What bothers Williard is that the city looks at his neighborhood as a blight, whereas he sees it as a poor neighborhood that looks like poor neighborhoods do. “You just need to leave some things alone,” he says. “It don’t need to be spiffy to provide affordable housing.”

At its core, this is Williard’s argument, a laissez-faire attitude toward real estate. He understands the value in worthless property. He has spent more than twenty years repeating this position to anyone who will listen. Now, confronted with rumors about his future, Williard admits he’s considering selling off the majority of his properties to a potential buyer, a man named Robert Adams. “At my age, it’s either time that I put somebody in position to manage them or sell them,” Williard says.

Williard’s critics will believe that when they see it happen. The contentious landlord has refused to give up, despite the small fortune he stands to collect.

“His first wife gave up on him because of it,” Pickett says of his client’s unyielding convictions about City Hall. “He has certainly been depressed at times in the past and wanted to give up, but has always rebounded and decided it was better to fight than to let them win.”

Williard himself won’t admit self-doubt. His divorce, he says, was the result of personal issues, though he allows that his convictions didn’t help. “She got tired of it,” he says. “She couldn’t see an end to it.”

Williard turns right and stops in midsentence to point out a crack along the wall of a rundown little home. “I’m sure that if I owned that property, I would have been cited for that,” he says.

Less than a block later, he passes an empty lot with grass growing out of control and an ugly metal fence. “Now if that were mine, I would be cited,” he says and drives on.

After years as City Hall’s favorite target, slumlord Charlie Williard turns the tables.

Dec. 3, 2003

Pitch, Article: Slumlord-Charlie Williard

You call me a slumlord. If I am a slumlord, what do you call the property owners next door to me whose property is much worse. Is it because I have been targeted and cited by the city and the neighbor hasn’t been cited?

Come on Casey, I thought you would be a little more even handed than that.

I also think the cartoon of me p__g on city hall was in poor taste.

Besides you got the wrong building. I don’t feel that way toward city hall. They provide many good functions and the vast majority of people there strive to do a good job for our tax dollar.

Slacks, a few sizes too big-five grubby fingers-most people only have four—grayish strands dangle from his nostrils—come on Casey, journalism can be more tactful than that. The thick billfold of money-you can get me robbed with that kind of talk.

Driving through pouring rain, daughter getting wet, me half leaning out of the cab—yes she got some water in her face, not drenched–only my arm out side-come on Casey, lets not embellish it too much-leaning half out of the cab —???

The house for $250, collected rent for years. I guess I should have pointed out to you that they have to be fixed up and maintained over the years.

Pornography-guns, did you see either here, or even a pin-up or an interesting calendar?

Two properties is such disrepair that the city tore them down—they had fires in them and I just couldn’t generate the money to fix them. They were very repairable but the city wanted them fixed quicker.

Fighting gentrification-I am not fighting gentrification. I am fighting the city that has weighed in on the side of speculators and investors that are taking the poor man’s housing because it is a money maker.

Gentrification is a movement much like urban sprawl. Let it be. You can’t control it. Let it run it’s course. Just let the government stay out of the fight on the money man’s side. Let the laws of supply and demand work..

The warehouse-scrap wood- working on it-a lot of good lumber there also, gathered for repair work.

You didn’t touch on the issue of the man next door, Kip Wendler wanting the ground for parking for his building and cutting the trusses so as to make sure my building would be torn down, using the city to enhance the value of his property at my cost.

Shock-prone van-minefield alleys???-kitchen appliances and houses that appear to be rotting from the inside-were any of them mine?

The rest of the article is pretty good. The real issue is money. The man with money wants to buy low and then fix up and run the poor out so he can live in an upscale area with no or low crime.

Sorry, this is inner city and there is more crime here because there are more people here and some of them are more prone to crime than in the suburbs. And when it takes up to four hours for the police to respond to a home burglar—?

I feel for the fellow that bought in and has spent $25,000. However he thought he got a bargain and was gambling on it being worth a lot more and seems to be working on making that happen by bothering anyone that isn’t fixing up to his standard. That also includes running out the rentals. I don’t think that is very fair.

Now the question no one seems to want to answer—where do we put these lower income people that need low cost housing? We can’t leave them here because “gentry” wants this area and the city will help them run the poor out. And the developer can make bundles rehabbing these older areas. Is there an answer other that than to just leave some thingsalone?

Until the early 1980’s property prices remained fairly stable and didn’t rise very fast.

Sence then prices have gone crazy, doubling-tripling-even a thousand times and this

leaves the lower income people in dire straits.

It is a tremendous money maker, especially when you can get the city to help you in controlling the increasing price spiral by using codes to up-grade property all around you.

The answer of course is subsidized housing and of course the cost is on the working man who pays the bill and the developer gets rich.

Dec. 5, 2003

Pitch: Slumlord, Charlie Williard by Casey Logan

Rental property is interesting, if you tend to it like a devoted husband would like to care for his loving wife’s kitchen you won’t survive. You have to provide the needed service and make money or get out. A rental unit is not a show piece like a show car.

It is like any other business in that everything is never perfect. It is even like a relationship. Two people can pick each other to death, or they can give and take and get along. Boss and employ relationships are the same. Tenant and landlord relationships are not any different. Rents are not always on time. Perfection is a word.

Home-owned properties have code problems too. A city inspector once bragged that “she could find a dozen things wrong with any house”.

There is a housing surplus here indicated by the Star having plenty of rental ads. Therefore a tenant can pick and choose, thus not having to accept a really bad place.

I have to maintain a certain standard or eventually be out of business, the law of supply and demand operates. I have some long term tenants. I also have some re-rents.

I do not run slumlord property in that I milk them for all they are worth and let them fall down. I mortgaged two properties recently and they appraised well. Check my website for pictures. www.affordhousing.com

I rent decent, safe housing to people of modest means at modest prices. I have to maintain some standard or face too many vacancies.

About ten years ago a man got mad at one of my tenants over an on-street parking dispute and to put pressure on the tenant, he took a listing of my properties to the city wanting the City to cite me. It seemed like a good thing for the city to take a look. It has been a witch hunt ever since. Properties all around mine are worse but not bothered.

The citations are usually minor, a missing down spout, trash and debris, storage of unapproved items, a car not tagged or parked on a non hard surface, pealing paint, a cracked window. Many of these things we would have gotten to in time anyway. And many times something across the street would be worse. The two houses torn down were fire jobs and I couldn’t fix them fast enough for the city.

The 303rd conviction–go look at 1100 east 33rd. Storage of un-approved items. Now look across the street at 1115 east 33rd- ??? And that man has been one of my critics. You can see pictures of this on my website. Kip Wendler, the man above, called the city on my warehouse because he wanted the ground. He needs parking for his building. He thought that if he could get my building torn down he would get the ground cheap.

The unfavorable court ruling: the city had wanted the building at 1103 Grand torn down or sold. The appeals court ruled against the City.

I think you did a pretty good job in the last part of your article as you quoted me saying that and that and that is worse than mine, though I don’t think any of them are rotting from the inside. I think that does indicate that my properties were singled out and cited when others were bothered.

A point you missed is that as people buy into these older areas at low prices, then spend bundles upgrading, then want their neighbors to upgrade; this pushes the prices up and the poor have to leave. Many of the poor don’t make $25,000 per year and they need low cost housing.

Is it fair for the man with the money to kick the poor out of their affordable housing?

One point I thought I had pushed and was missed: law and order. We put me in jail for pealing paint (in a jail with pealing paint, a leaking roof, and many other code violations) but we can’t seem to do anything about the street crime problem.

Colt 45 in the can in far more deadly that the concealed gun. I don’t carry or want to carry, nor do I have a pin-up. I also do not expose my self at city hall, wear my pant’s crotch down to my knees or consider myself snot-nosed.

I also do not feel that I cause blight, therefore I am not the Captain there-of.

Charlie Williard

Dec. 9, 2003,

Nate Pare’.

As the deadline approaches I wish I could sit down and talk with you.. I would like to ask, what is the advantage of demoing this building? What is the gain?

If the issue hinges on me not appealing a ruling last year, then tearing the building down does not make sense. We do not cut my arm off because it did not heal fast enough.

If tearing it down is about winning an argument, that is wrong too. I want to win but not for the sake of winning the argument. I want to win because I can fix it economically and I will have a storage building that will be very useful to my business.

I would even say that the city should want me to have this building for my storage. The city has cited me more than once for open storage, if I have this building for storage, the problem is eliminated A win-win situation.

I will assume that you read the Pitch article. I wrote a reply objecting to being called baggy pants and snot-nosed and then realized those issues are’ not worth answering.

I am answering the 303rd conviction issue with a picture of the lot across the street from the warehouse which indicates how I am singled out for citations. It is on the web site now. My website has generated a hundred hits since last Wednesday. I am wondering how many more hits will register when my reply is printed.

I am also wondering how Kip is reacting to the picture being somewhat in error and how he will react to my letter to the Pitch. And then is the City going to cite him?

I am contending that the appeals court ruling should be binding on this case, that it is not a dangerous building.

I also contend that I can repair it economically, that it will be a good, sound building for many years to come. That it will be an asset to both me and the City in that it will serve my business needs and pay taxes.

We have most ofthe materials there to finish the job. We have the know-how. We have the engineer and his drawings. And we have the City permit. Being slow should not be the factor. The building is not open to the public.

I would like as answer in writing to this letter showing me where and how I am so wrong.

Charlie Williard

Dec. 12,03

The Honorable Judge Williams

Dear Sir,

Judge Cagle made me famous ten years ago and nothing has really changed. And nowyou have added to that fame in the 303rd conviction. I say nothing has changed because I have just bought two houses in worse condition than my houses right beside them. I’m sure you didn’t see this coming. I didn’t. In fact I was quite incensed by the article depicting me urinating on City Hall. Besides they got the wrong building and showcased me in front of the wrong warehouse. But every one I talk to loves it.

Kip Wendler, one of my critics, who owns that building, is perturbed too. Wellia-te-da, he started this mess by complaining to the city in the beginning. He also owns the lot across the street that is stacked with open storage. People in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

The article was printed in eleven sister magazines from California to Florida. Now if you would like we will figure out a way to get your name in it, who knows, a federal judgeship-

Had you known ‘the rest of the story’ you might have ruled different-or thrown us both in jail. Or thrown it out as being frivolous. A judge recently said “I can only make good decisions in am given good information’. In real crime I understand people are discouraged from coming to court with ‘un-clean hands’.

We couldn’t present the politics of the neighborhood, the crime problem and the squabbles of the business men trying to one-up each other to make the dollar; and their use of codes as a weapon against each other.

I bought two properties recently, the third in the last fifteen years I think, and both are beside properties I already own and both are much worse condition than mine. One of them had been a drug house. We called Dart but like the house that operated next door to me for ten years, we couldn’t get anything done. You can see pictures of these houses on my website. www.affordhousing.com

The problem of selective enforcement is magnified with the anonymous complaint. And then add to that, the city-or inspector generating complaints pushed by neighborhood associations wanting to up-grade, and the money angle. Mr. Mudd and Ms. Boley bought in here because they see dollar signs. And those issues can’t be made a part of the court case either.

In 1980 an investor here in Hyde Park, Tom Brennen, bought breakfast for the code inspectors and gave them a pep-talk-go write up ever thing you can. He, along with several of his associates went broke in spite of being able to use the city for their personal agenda.

The Pitch article mentioned neighborhood groups bragging of the number of houses they had returned to single family status—what about the lower income tenants being displaced? Does any body care about them? Not when there is money to be made! They can go to hell as far as these money people are concerned.

The Doonesbury cartoon shows this scenario and the recycling of the whole situation. I don’t think you can control it and I think the government should stay out of it, especially on the money man’s side.

My wife and I were recently hit by a hit-and-run driver, no insurance or tag. This was Nov. 10. The case comes to court in March. And if he asks for a delay–??? But housing–next week—- and if I am at MCI baving missed court, no release on personal Recognizance and the bonds on property owners??? Where are we going if we own property? What about a property bond?

This is very special treatment, the common criminal is not herded through the system nearly as fast as us hard working, tax-paying, other-wise law-abiding, housing code violators, and then, only those of us that have been targeted. And I have yet to see the prosecution bring in an actual victim of any of my crimes. It is all theoretical.

In a damage suit one has to prove damages—I can see it now, ‘I didn’t make the profit I might have made if Williard had thrown in with me and kicked all the lower income people out.’ Would you find me liable in that scenario?

This is a real political football. Look up my website, letters, pictures and all, even the Pitch article. We are learning to take pictures.

And the jail, Judge. There are plenty of violations out there but the most glaring problem is the phone charges and that the phones don’t work a lot of the time. A collect call should not cost $3.00. Those people need to be able to use the phones. I understand they only cost fifty cents and a dollar in other facilities.

Charlie Williard

Charlie- we thought you’d get a laugh out of this one: it is exactly what you were saying to us when we were talking one day , this past summer.

Ann Newman

Winnipeg, Canada About 1980